In May 2025 I had the pleasure of travelling again to South Africa as part of my role as Manager, Education Partnerships, with SAE Creative Institute. On my last day there I had one afternoon to be a tourist in Cape Town: these photos were taken at the tip of the African continent, from the spectacular Table Mountain, known as the “sea mountain”, Hoerikwaggo, by the original Indigenous inhabitants of this area, the Khoekhoe people.

BULA!

As soon as visitors arrive in Fiji, they are greeted by the biggest smiles, and cheerful greetings of Bula! Welcome to our home!

Beqa Island, south of Viti Levu

When my partner Alexander and I went to Fiji in August 2023 for a well-earned holiday, we were far from thinking that we would soon be planning our next collaborative film project there… It is safe to say that Fiji and Fijian people stole our hearts, particularly the Naceva Community, on Beqa Island. Here is the story.

The Naceva Village and broader community on Beqa Island in Fiji are the finest human example of compassion, fortitude and resilience. On the 3rd August 2023, we were welcomed as visitors to Beqa Island from the proximate Royal Davui Resort. Many of the Naceva Community work at the resort in a variety of professional roles.

The reality is that many visitors to this beautiful part of the world come here to holiday and spend their money, yet as my partner Alexander and I noted, many conveniently side step the brutal reality of history that presents itself in this part of the world, and often choose to ignore the current challenges facing the community.

During our visit, we were entertained by the school children, we purchased beautiful crafts and artworks from Naceva women, and organised soon after to return on the 8th August 2023 for a full and proper introduction to the Village Elders, members of the Naceva Development Committee, the Methodist Reverend Mesake Vakaloloma, the school Head Teacher and School Principal and Aparama Qaluma Ratubaka, our key communications contact. We made a small contribution of $50 AUD to the Naceva School on that first visit.

The village of Naceva, Beqa Island

A bowl of Kava

On Tuesday 8th August we were taken from Royal Davui across to the Naceva Community, Beqa Island by two Naceva Village leaders, “Sparky” Eminoni Galivia and “Arpi” Apenisa Kuruiwaca who had organised for our first formal cultural meeting with the Village Elders, members of the Naceva Development Committee, young Village men and the Methodist Reverend Mesake Vakaloloma.

We brought with us a large pre-arranged package of Kava which we had purchased to share and drink in the Village Community Centre. We listened to the traditional welcome carefully and were honoured to be welcomed formally to the entire village and community. Alexander and I both made formal introduction statements of the work that we do and have done through many years in Indigenous communities throughout Australia and our lived experience in many parts of the world.

We listened carefully to the key challenges that the community is facing and have understood their determination to work on projects with those willing to engage in constructive and meaningful ways.

A home in Naceva village

School donation, Naceva

During the intermission of our meeting with the Village Elders and community, we were taken by Aparama to meet again with the Head Teacher, Selai and School Administrator, Saula of the Naceva Community School.

Our small donation was a small token of appreciation and it was presented to us as means for them to raise well needed funds for the education of the school children.

In listening to the Village Elders and the men of the village we learned that the most pressing challenge for the community is the construction of a sea wall buffer to counteract the prevailing swells and currents that buffet the front alluvial plain of the village, especially during monsoon season. This is all a result of global warming and is a full attributed erosive factor that is causing an “Out of Bounds” area adjacent to the school, endangering the lives of the community members. Every month, each villager employed at the resort makes a financial contribution to the seawall, which is being built by the men in the community.

Climate change is an issue for most Pacific Islands, and there are thousands of villages like Naceva which are threatened by the rising tides, even if they are somewhat protected by the coral reefs.

Coral reef, on the south coast of Viti Levu

In discussion with Aparama, Alexander and I declared we would contribute our principal foundation contribution of 5000 FJD ($3,453.52 AUD) to the Naceva Seawall Project through the Naceva Development Committee. This was met with great enthusiasm as it immediately provides funds to purchase concrete to build the seawall blocks and employs the village men in the construction of the wall. We emphasised to the entire Village Development Committee that we are people of action and determination, not faith and hope alone.

School buildings, Naceva

Our core contributions, we consider, gainfully demonstrate our capacity and willingness to listen and to engage in activities which are ethically aligned with our Principles. In this case, we will listen carefully to the community, and map out a collaborative project, made up of different components, which will be able to be used for the much needed fundraising for the seawall project, and potentially for other school and community projects.

Our life purpose is clear - do well and do no harm.

Our business is about people and Country. We value connection and our philanthropic investments are guided by our Principles how we can make a difference in other peoples lives, not just our own. We consider community as Family and endeavour to listen carefully through the Kalara and Ngikalikarra emancipatory processes, mindful with eyes wide open of the challenges of an encroaching technological matrix for First Nations.

View from pontoon, Royal Davui Resort, Beqa Island Marine Reserve

Alexander went back to Fiji in September 2023, to make a short film about the Naceva Seawall Project, with works in full swing during his stay, and I went back with him in October 2023 to fulfil our promise to work with the Naceva Community to create film excerpts about village life to be included on the village website. We had the immense honour and privilege to live in Naceva, Beqa Island, for 10 days - an amazing adventure, far removed from the tourist experience, and were again very humbled by the warm welcome from the Naceva Community.

The video below was shot by Zak Tiko, from Naceva, on our last night in the village.

Many thanks to my partner Alexander Hayes who authored the majority of the content of this blog for our Oethica Website.

In November 2016 I had the amazing opportunity to travel to Kolkata, India, to attend a two-week intensive course on Environmental Humanities: Ecology, Culture, Intervention, led by Professor Stephen Muecke (UNSW) and Dr. Nilanjana Deb at Jadavpur University.

Prinsep Ghat, Kolkata

Photograph by Shantam Basu

I felt that this course would help me pull together my last discussion chapter for my PhD work with Nyikina women in the Kimberley, as our collaboration for the past ten years has revolved around conflicting notions of development and the environment. And I was not disappointed! Jadavpur University’s multi-disciplinary approach on the topic of Environmental Humanities is innovative and refreshing.

This was my first visit to India and an absolutely wonderful experience on every level. Everyone in the course, staff and students, went well and truly above and beyond the call of duty to make me feel welcome there, as the only international visitor apart from Professor Muecke. Dr. Nilanjana Deb took a lot of time off her incredibly busy schedule to introduce me to her beautiful city, as did other students in the class. Scholars, many of them Indigenous, had come from all over India, to learn but also to share what was happening in their respective homelands.

Jadavpur University is known in India to be quite an activist university, where students’ movements are very strong, as reflected in the graffiti work adorning the corridors of the English Department, where we were based.

I felt very privileged to be invited to hold an informal session with research students and staff from the Department of Comparative Literature, which houses the Centre for Canadian Studies, and to present one of the lectures for our course, based on my research work and the current situation in the Kimberley, during which I showed our film, Three Sisters, Women of High Degree. As part of the course we also undertook two field trips, one to the Kolkata ghats on the Hooghly River, a tributary of the Ganges, and to the flower markets, and another to the East Kolkata Wetlands.

Department of Comparative Literature, Centre for Canadian Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata

East Kolkata Wetlands

I have included below two ethnographies I wrote whilst in Kolkata, as well as the photographs that accompany them. I feel they best reflect my experience of the great City of Joy. I am truly grateful for all the amazing people I met and hope to continue working with for a long time to come. I have been invited to present at an international conference hosted by the Centre for Canadian Studies next March (via Skype), and to write an article for the Project E-QUAL Newsletter (an international collaborative project in the five key areas of Critical Thinking, Cultural Studies, Human Ecology, Natural Resource Management and Sustainable Development). And so the river stories from many peoples and countries continue to be disseminated around the world…

On an evening walk near the Hooghly River, Dr. Nilanjana Deb read us this translation of the monument beside the river:

"This monument is dedicated to the well-being of fish. It says that life, our life, is dependent on water, and to be aware of the importance of the beings that live in water. It is something that all of us should work towards, to increase awareness of our relationship with water creatures, and this is dedicated to them".

An Ethnography of a Pedestrian Crossing in Kolkata

Having been in India for all of three days, I am aware that my observations will remain somewhat superficial – I have not yet ‘learned to see, think, feel’ (Marshall, 2015), and appreciate the full reality of crossing a busy Kolkata road with the eyes, and ears, of a local. Participant observation (Malinowski, 1922) is useful, within limits – I must also acknowledge that as the ethnographer, I am very much an outsider in this space.

At first glance, there appears to be no rules. Through my Western gaze, the crossing looks like a noisy, disorganised, chaotic space. People cross whenever or wherever they have an opportunity to cross. This often involves much zigzagging between vehicles – it is never a straightforward affair. They may choose to use the crossing, but mostly, they don’t. Pedestrian red or green lights do not seem to be a factor in the slightest way. Unlike in Australia, where many cross the road while texting, or chatting on their smart phones, crossing a road in Kolkata requires utmost attention and concentration. Vehicle trajectories are unpredictable: they may change lanes at any moment. Because of this, and of their sheer number and mechanical power, one would think that vehicles are in very much in control of the situation.

Most people will wait for a temporary break in the traffic, make a dash to the middle of the road, and stop there until they can cross to the other side in a similar fashion. Others will attempt to cross, only to step back when prompted by an angry honk, and a car stopping abruptly within millimetres of their person. Some are more patient: perhaps they have more time. They wait longer, and proceed to walk to the other side, whilst talking to each other, but never taking their eyes off the road. Others bravely defy traffic and make a run for it on their own.

It seems that there is power in the masses – if a large group of people decides to move forward as one, vehicles do not have a choice but to let them cross. Care for the youngest and oldest is shown at all times: young children hold hands together or with their mothers; old people with the younger people accompanying them. A stray dog had also apparently worked out that it was indeed safer to cross the road in the company of humans than by itself. Having said that, one old man single-handedly managed to stop one bus, a car, and two auto-rickshaws by slightly raising his hand at them, walking slowly but confidently in front of the traffic with his four-leg walking stick, without even glancing at the drivers.

The chaos is only a superficial, first-hand impression. At no point did I feel unsafe crossing the road, particularly in the company of others. There is a prevailing sense of solidarity amongst pedestrians – haphazard groups form to cross the road and instantly disperse once on the other side, each person heading to their own destination. Vehicles will always honk as if in protest – but they will stop and wait.

Reciprocal recognition (Hage, 2000) occurs firstly between the pedestrians themselves: realising, perhaps unconsciously, that there is safety in numbers, if only momentarily, they support each other tacitly – ephemeral solidarity being, surely, the best strategy of survival for all on the crossing. It makes no doubt that drivers also recognise, and ultimately respect pedestrians, particularly the most vulnerable – if a frail old man can stop the traffic with a slight wave of his hand, the ethical foundations of the society I am observing cannot be questioned.

The mutual obligation between drivers and pedestrians appears to lie in the assumption that they are all trying their best to do what they are supposed to do at this particular moment in time, fulfilling the responsibilities they each have in society. Pedestrians, however haphazard their crossing of the road may appear, have an obligation to be careful, and to not push the limits of safety too far. Drivers, on the other hand, have a responsibility to not misuse the power that they have been given by having control of a motorised vehicle.

A busy pedestrian crossing in Kolkata reminds us that tacit trust is the foundation of ethical society: if each individual recognizes the others’ existence, and fulfills their own responsibilities, everyone, including humans and vehicles, can coexist peacefully, and get on safely with their day - including the stray dog.

A Photographic Essay of the Kolkata Ghats

Baghbazar Ghat, Kolkata

Baghbazar Ghat is an old ghat, as yet apparently untouched by modernisation, unlike other ghats along the Hooghly River in Kolkata. Wide steps leading down to the Hooghly are covered in slippery, thick, pungent river mud. Flowers, leaves, colourful receptacles, tree branches, water hyacinths, shreds of vivid materials, dismembered idols, plastic plates and cups, pieces of polystyrene, and plastic bags, mingle in untidy heaps, deposited there, seemingly haphazardly by people, storm water, or the river itself. Sadly, worshippers have recently taken to placing their flower offerings to the dead in plastic bags.

The Hooghly, a tributary of the Ganges, is a place to farewell, revere, and remember the dead – small, spontaneous shrines flourish in elaborate niches at the top of the ghat. Paintings and representations of Shiva adorned with flowers, necklaces, and bright fabrics, sit side by side with a statuette of his son Ganesha, the God with the elephant head, and a series of wooden, brightly painted mask figurines. Another niche below contains the statue of a cobra snake – a symbol of death and rebirth, perhaps? For at the ghat both life and death are closely enmeshed – and the Hooghly is the link between both. Nearby markets sustain the livelihoods of the people who survive, from death itself – from selling balls of river mud for ceremonial practices, or the plastic containers that will allow worshippers to take some of the holy river water back home, through to the idol figurines, necklaces, jewellery, flowers, and clothing the people will need to perform those death rituals.

At the Nimtala Cremation Ground a cremation ceremony is about to start. People are waiting inside, while the wood is being carried in. Here the cremation still occurs traditionally, although many crematoriums around Kolkata have now opted for electricity. The ground itself is wide open, looking out onto the river, and houses the Tagore’s Samadhi Memorial – a sense of peace and quiet prevails. People say that when the smoke comes out of the chimney, the soul of the dead person has been released. Unlike in Western countries, where death is mostly hidden and feared, death here is everywhere: the hearses transporting the dead have glass panels, and the person awaiting cremation lays covered only by a thin, colourful cloth, and flowers – this visibility perhaps a better way of accepting death as part of the journey of human life. On the day of our visit, the relative quietness and peace of the cremation ground is interrupted by a string of announcements and speeches blaring out of a loudspeaker just outside. A celebration is underway, officials at the ready in their bright white uniforms, a small crowd gathering: they are marking the anniversary of the first air-conditioned hearse – even the dead can travel in comfort now, whilst producing their own greenhouse emissions…

The Nimtala Cremation Ground, a place of death, spawns life. Ghettos of metal and timber huts sprawl near abandoned warehouses, temporary lodgings only: many traders have a house in a village somewhere, and have come here to earn a living. Like at Bahgbazar Ghat, people have set up shops to cater for the dead – and the living. The usual trades have sprung up: idols, jewellery, flowers, clothing, food and drink stalls. Reflecting changing times, some have also been quite imaginative – a photographer has set up shop, taking photographs of the dead and their family just before cremation. He is said to be doing very well.

The Art of Making Masala Tea

At a small hut near the Nimtala Cremation ground a crowd has gathered. People take their seats on wooden benches expectantly. An old man is sitting in a small, dark recess, in the midst of old pots and bottles. A painting of Shiva, the all-powerful god, at the back of the hut, appears to watch over the proceedings. A boiling pot sits on a bed of hot coals. A small electric fan on the ground, controlled by a switch at the back of the man, controls the temperature of the coals, for it must be just right. A mixture of milk, water, and masala are boiling in the pot. The old man is stirring it quickly. When it comes to a boil, he takes it off for a few seconds – then puts it back on, bringing it to the boil slowly again. The old man adds holy basil to the mix. Flick of the switch, quick stirring, lifting – and again, several times: it is all in the wrist action. The pot is stirred again, cardamom pods added, then rose water. The sequence of events is a wonderful, rhythmic choreography, of gestures timed, rehearsed and performed hundreds, perhaps thousands of times. Nothing is left to chance. In a swift, final move, the pot is taken off the coals, another pot held in the other hand, and the mixture poured from one into the other, from high up in the air, into the pot below – to cool it down. The tea is served in a terracotta cup. Everyone sits and savours it for a few seconds, before going back to their respective occupations. An ephemeral, peaceful, quiet moment shared by friends or strangers, away from the chaos of the street.

Across the street, a man is sitting in the sun, on a rug on the ground. He is reading his newspaper. At first glance a newcomer like myself may not realise what his trade is. On closer inspection, homemade cards lie, in a line, face down beside him. Almost unnoticeable at first glance, a small cage sits in a corner of the rug. In it, a lively parrot. It has been trained, perhaps through gentle persistence, and food rewards, to pick six cards for the odd tourist, or passer-by. The man is a fortune-teller, and his companion the parrot, the source of his livelihood. Unlike the masala tea maker, the outcome of this activity is much less certain. In spite of the offerings of seeds, the parrot is not always willing to work – sometimes it decides that now is not the time, and the fortune will go untold, leaving the traveller, myself in this instance, somewhat disappointed, and the fortune-teller to go back to his newspaper, hoping for a perhaps more successful outcome - next time. For there is a lot of waiting at the markets – chaos suspended, for some, in the midst of the overall noisy traffic rush: sellers wait in their stalls for prospective customers; ageing, wrinkled, wiry hand-rickshaw drivers bide their time in the sun until their next ride; beggars, infirm, blind, old, or ill, stand, hopeful, with outstretched hands, on the side of the road, hoping for a couple of rupees; stray dogs and goats roam, waiting for sustenance that may never come.

Further on, and the intensity of the flower market assails the newcomer’s senses: the smell of tube roses attracting hundreds of bees, the vivid colours of the large flower heaps, the throngs of bodies in narrow spaces, the din of people calling out to each other amidst the hubbub of negotiations, the impatience of porters running up and down the alleyways, carrying their colourful loads on their heads… Wherever I go, I seem to be in the way. A man sits down, carefully threading vivid orchids onto a fine metal thread. Again, the gestures are precise, the hands self assured, the eyes never averting from the task at hand, in spite of the business of the surroundings. In the midst of animated bargaining between wholesalers and retailers, weighing, ordering porters, counting money, appraising merchandise, and more bargaining – there are hundreds like him. In this well-ordained chaos, everyone, human and non-human, has a role to perform. Bael leaves, blue flowers, and wild plants are sold for the worship of Shiva, and red hibiscus for the Goddess Kali; white lotuses, the symbol of enlightenment, will be offered to the Goddess of Knowledge, Saraswati, or to teachers and mentors, as a gift of appreciation; mango leaves are strung for home decorations; loose flowers are neatly wrapped in wet leaves to take home; tiaras and garlands await the prospective brides and grooms, while baby coconuts will be sold to hang above entrance doors, welcoming people into the home. New additions have recently come to the market: orchids, carnations, in ready-made bouquets, even artificial flowers, are now being flown in from Bangalore and other areas. This is a fluid, ever-changing space: a market stall during the day turns into a shelter at night – for many traders, this is the only place they call home. Against the original supporting structures, the colonial iron pillars, they have built brick walls and timber frames, to make the shacks more comfortable. Just outside, at the Mallick Ghat, they go about their daily ablutions, unperturbed by the traffic on one of the main Kolkata bridges, right above their heads.

Flower Market and Mallick Ghat

Sunset on the Hooghly River

At the Kolkata ghats, these livelihoods are more than survival mechanisms, perhaps also more than crafts. They are, in a sense, art forms, or ‘poiesis’ in action (Heidegger, 1977), at times relying on precise gestures, crafted and re-crafted, time after time, or at other times, simply imaginative, poetic ways of re-affirming life, or creating solace – from death. At the Hooghly River ghats, the Nimtala Cremation Ground, and the flower market, both life and death are closely enmeshed and the river provides the link between them, and people. These networked local ecologies, economies, and histories are ecosystems in their own right: they are all inter-dependent, deeply relational, and collectively produced (Haraway, 2016, p. 49). Every component needs the other – flowers, tea, humans, parrots, river, stray dogs, all need each other to function. They are sympoetic – they evolve and change with events, seasons, ceremonies, people’s imaginings – they are a tacit understanding that the river, humans, and non-humans all need each other to transcend the boundaries of life and death.

East Kolkata Wetlands

For film excerpts relating to this blog, and news about our upcoming film, Protecting Country, please go here or scroll down to the bottom of this page.

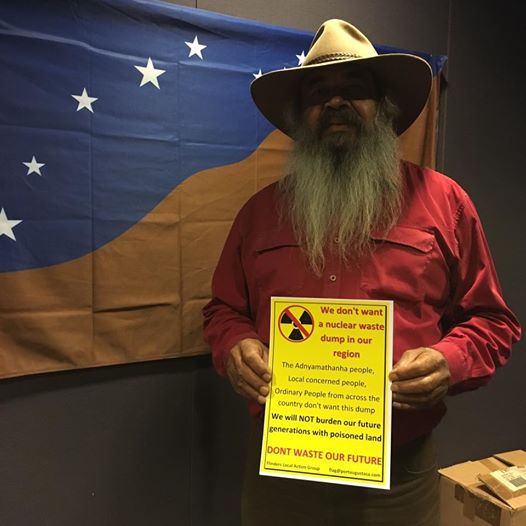

Over two years ago, my partner Alexander Hayes met Bruce Hammond, of the Tanganekald & Western Arrente people, South Australia, who brought to his awareness the ongoing struggles and challenges that his people and other Aboriginal communities face, particularly in light of the South Australian proposal for a nuclear waste dump in the Flinders Ranges. With over three months of logistics and planning, and at Bruce's invitation, Alex and myself will be travelling through many different communities in South Australia, listening to the voices of people on country, who have not been consulted by the government in an appropriate manner.

So on September 24th we started our journey from Canberra to South Australia.

Our road trip took us through Wagga-Wagga, the Hay Plains, Benanee Lake, Balranald, Mildura, finally arriving in Adelaide on the morning of the 26th.

On 26 September, 2016 we had the pleasure of meeting and interviewing Karina Lester, Co-Manager and Aboriginal Language Worker at Mobile-Language Team, at the University of Adelaide. Karina is the daughter of well-known Yankunytjatjara Elder and Activist Yami Lester, who was blinded by the 'black mist' from the first Atomic Test Bomb at Emu Junction, South Australia.

Karina told us that the idea of a nuclear waste dump in South Australia is not new - her grand-mother and her family successfully fought against it back in the 1990s. But now it is on the agenda again, and Aboriginal communities whose land the nuclear dump would be built on are not being properly consulted. Even though the South Australian government is sending representatives to a hundred different communities, under the guise of consultation (Get to Know Nuclear), they are not engaging language experts and interpreters to communicate directly and effectively with these communities. Aboriginal people are therefore not getting all the information on the nuclear waste project, thereby contravening the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on Free, Prior and Informed Consent.

Well, September 27th turned out to be a full day! We had the great privilege to interview Tauto Sansbury, Steven Harrison, and Bruce Hammond about their perspectives on the nuclear waste dump.

Tauto Sansbury asked, with good reason, why it is that no other country seems to be putting their hand up for the 'privilege' of getting a nuclear waste dump, if it is that great an opportunity!

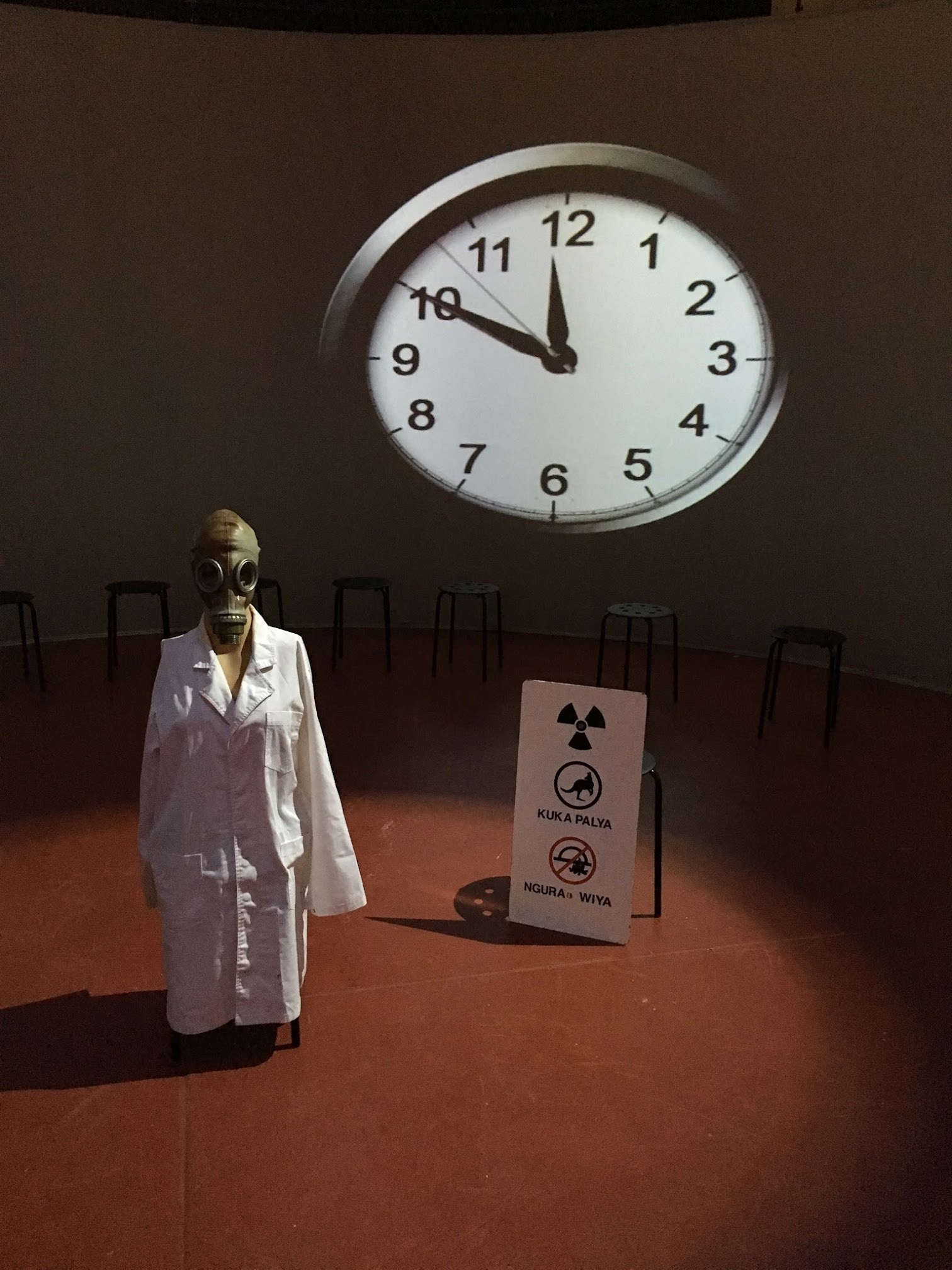

Senior Corporate Officer Ruth Miller at the Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute then welcomed us with open arms to show us through the amazing 'Nuclear' exhibition retracing the stories of the people affected by the 1950s British nuclear tests in South Australia, through videos, archival footage, paintings, and creative objects. There, we interviewed artist Steven Harrison about his perspectives on the nuclear waste dump and how his art practice has been underpinned by a need to tell the stories of the country affected by the British Nuclear Tests. We also sat in the eye-opening '10 minutes to Midnight' 360-degree art installation.

In the afternoon, Bruce Hammond talked to us about the ongoing cultural genocide of Aboriginal people: in his opinion, the nuclear waste dump is simply a new act of dispossession in a long series of genocidal acts perpetrated against Aboriginal people since colonisation - taking away land, language, culture, separating families, dividing communities, and now ignoring cultural protocols and custodianship of country, putting money first, appropriate consultation last - politicians come and go, he said, but Aboriginal people are still here, fighting on...

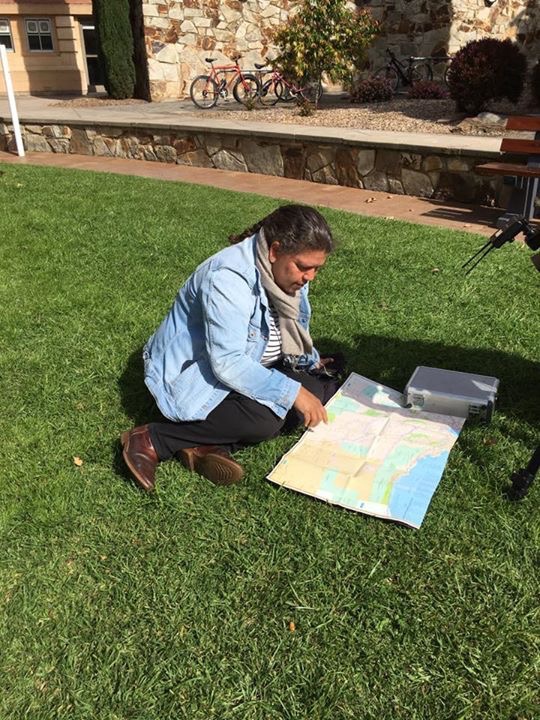

With Bruce, we planned our trip ahead - with invitation, we look forward to connecting with Elders and community as we travel from Adelaide, through Port Augusta, Quorn, Hawker, Leigh Creek, onto Nepabunna tomorrow. Weather permitting we will 4WD (Nissan Patrol) across to Marree onto Cungmurka, William Creek and up to Oodnadatta - two days filming and back via the Kempe Road, through to Coober Pedy, Coondambo, Woomera, Port Augusta then back to Adelaide...

I am now sorting the interviews and putting together footage as we go... But I need to get ready for the big drive tomorrow! So long...

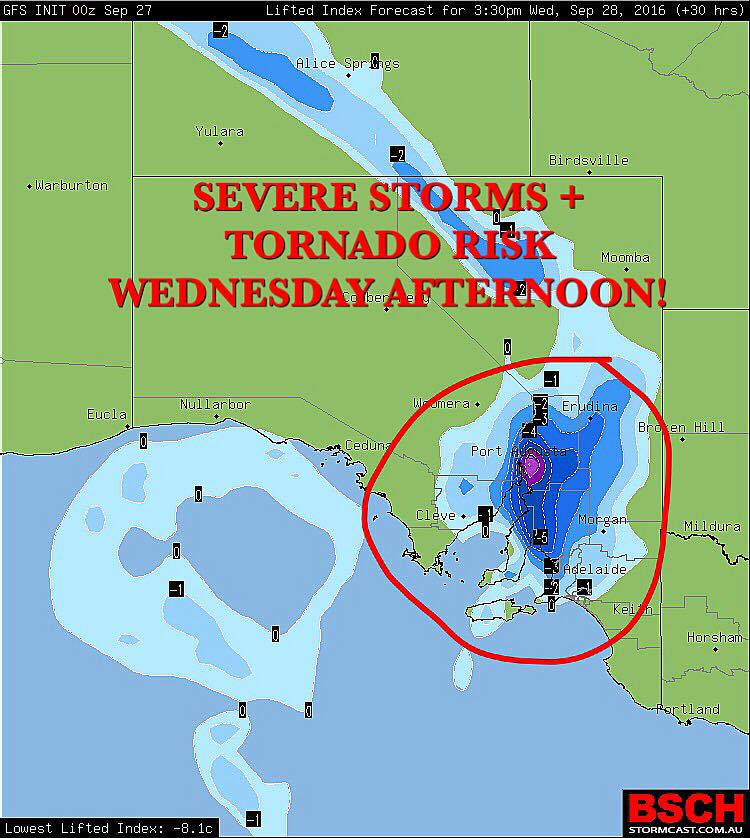

Ok... Long time no see! So many stories to tell... The reason for the long silence on this blog was the fact that we ran into the 1-in-50-years storm in South Australia, which made news headlines for days as it caused extensive damage, flooding, electricity blackouts and road closures around the Eyre Peninsula... Right where we happened to be!

On September 28th we started our drive from Adelaide to Port Augusta, knowing from the news, and just by looking at the ominous skies, that the storm was looming. Trusting what our guide, Bruce Hammond, had said, we made it safely to Port Augusta - through heavy rain, then rays of sun shine, black skies over turquoise waters in Port Germein, and even stopping for a quick look at Nessie half-way...

In Port Augusta we drove straight to Umeewarra Media, where Adnyamathanha Elder Vince Coulthard was expecting us. Vince is the Chairperson of the Adnyamathanha Traditional Land Association, and the Director of Umeewarra Media Aboriginal Association. In his interview, Vince explained to us the significance of the Adnyamathanha Flag, and his strong opposition to the nuclear waste dump being located on Aboriginal people's land - why should Aboriginal people be expected to give over their land, yet again, he asked, when they have already given so much, particularly in South Australia, with the original nuclear tests, and the mining industry? Next we met Stephen Atkinson, from Port Augusta, who commented that both the Federal and State nuclear waste dumps proposals could well be hiding something else - a push for nuclear power for South Australia maybe? We finished our two interviews just in time before losing all electrical power due to the storm, and retreated to our small hotel, with no electricity, to ride out the storm... Knowing that in the morning, we were going to meet Vince to drive out to Yappala Community, where the McKenzie sisters are fighting the Federal proposal of a low-level nuclear dump on their traditional lands...

After a very, very windy and stormy night, and still with no electricity, we drove out of Port Augusta, through Hawker, to Yappala Community, early on the morning on September 29th. The Federal Resources Minister, Matt Canavan, was expected to meet with the community but his flight had been cancelled due to the storm... Fierce winds and extremely cold weather greeted us as we got out of the car - soon tempered by the arrival of three brilliant, dynamic, and outspoken sisters: Regina, Vivienne, and Heather McKenzie. Alwyn McKenzie, Michael Anderson (ATLA), and other government representatives were also present. We quickly got a run-down of the situation by Regina McKenzie, before being ushered into a cold, dark room (no electricity there either), where the meeting was going to take place - the minister, instead of being there in person, was about to link in by phone. Vince and the McKenzie sisters proposed that I should film the meeting, and there was a consensus that I should be allowed to film, even from the minister and his staff, which I did, of course, for more than an hour. The attitude of the minister and the government, and their lack of consultation, again, revealing a very poor understanding of the importance of country for Aboriginal people. Regina explained how they had been able to secure a $50,000 grant from the State Government of South Australia to map several songlines on their traditional lands, working together with landowners on this important project, only to learn through a news bulletin that this same country had been earmarked for a low-level nuclear waste dump, with no prior consultation, and no mention of it by the landowners concerned... This footage of the meeting is riveting!

I then interviewed Regina McKenzie, who reminisced how her father walked with her on country, many many times, telling her the stories and songlines for their traditional lands... Exactly where the nuclear waste dump is being proposed, without consultation. Alwyn McKenzie, on the other hand, talked about the fact that although he did not trust the international intermediate and high-level nuclear waste proposals by the State, the low-level nuclear dump may be an acceptable thing, on the condition of it providing economic benefits to his community and people. Having had a close family member undergoing extensive cancer treatments for a number of years, he said he understood the necessity and the need for such medical treatments, and that the waste they produce should be safely stored somewhere - as long as Aboriginal people were consulted about it and told all the facts. All present at the meeting agreed that the lack of consultation by the Federal Government was the sticking point, and had to be remedied straight away.

After refuelling in Hawker in one of the only places with a generator, we headed out to Nepabunna Community, a former mission, where both Bruce and Vince had told us to go to. Keeping slightly ahead of the storm, we travelled for about 60 kilometres on a dirt road, stopping to film kangaroos, emus, and brumbies, heading towards Nepabunna with no idea of where we were going to spend the night or who we would meet there - only guided, again, by what we had been told. Arriving in Nepabunna as the storm was about to set in, we were advised by Mick Coulthard to retrace our steps back two kilometres to Iga Warta Community. There, on night fall, we were greeted warmly by Terry Coulthard (Junior), who offered us a spot in front of a lovely warm fire inside, some cooking implements, great company - and an invitation to stay the night in one of their luxury safari tents. A bowl of soup later, and interesting conversations galore, we were feeling much more relaxed and already planning the day ahead.

And what a day September 30th was... Getting up early after another night of stormy winds, we discovered, disappointed, that light rain had set in. In the common eating area, where everybody had again congregated around the inviting campfire, we met Terrence Coulthard (Senior), who runs Iga Warta and told us interesting stories as to why people are attracted to the Flinders Ranges - one of the oldest places on earth. Some people, he said, know something is going wrong with the world at the moment. To get answers, they instinctively end up going back to the origins of it all... Even French people like me go back to country to find answers.

As nice as it was sitting around the campfire, reality set in. Iga Warta had no electricity, and with only one generator going, it was an absolute necessity to get some firewood to keep everyone going - many stranded travellers had taken refuge at the community at the height of the storm. Taking a couple of guests with us, including Mia Knight, from Western Australia, we followed Elder Sharpie Coulthard to the hills to collect some firewood. With the rain and clouds, my hopes of getting shots of country had been dashed. But the fierce, cold winds set in again, and the sun miraculously came back almost at the same time as we returned to Iga Warta. Having collected enough firewood for the day, Sharpie told us he would come with us to Arkaroola to tell us the Adnyamathanha story of uranium. We stopped many, many times along the way to shoot some footage of the rich, amazing landscapes of the Flinders Ranges: hills, plains, creeks, rocky outcrops...

Sharpie took us to a beautiful place on country: sitting in front of the most amazing cliff face, he told us the Adnyamathanha creation story of the snake who drank too much sea water, went back to his country and became sick, vomiting in many places... This is where uranium is found - and Aboriginal people always knew to leave it in the ground, where it belongs. But the uranium used in the Hiroshima Nuclear Bomb had come from Arkaroola... Sharpie explained that Adnyamathanha people are just sad now, because no matter how much they have tried to explain things and educate white people, they are still being dispossessed, not consulted, and not listened to - the nuclear waste dump being just another chapter in a long story... Walking with Mia, Sharpie then explained the significance of water for the land, and how mining takes away the water from country. This poignant interview with Sharpie will ground our film within country: this is where the story begins, and where it ends. That night, back at Iga Warta, we were told many more stories of dispossession and survival, this time through songs around the campfire... Thank you Clarrie Coulthard, and James Butler, for sharing your songs with us and allowing us to record them. Iga Warta is a magical place: if people come to listen, and learn, they will be welcomed there with open arms. We cannot thank Terrence, Sharpie, Clarrie, Christine, James and Ty enough for the wonderful time we spent there over two days and two nights. Unforgettable.

We had to get up early the next day (October 1st) as we knew we had quite a bit of driving ahead... Having been unable to continue to Oodnadatta as planned, through William Creek, because of road closures from flooding caused by the storm, we knew we had to get back to Adelaide, with the feeling, though, that the story was complete, for now. We had gone where we were meant to go, and met the people we were meant to meet. Before we left Iga Warta, we interviewed Ty Butler, who gave us a young Aboriginal person's perspective on the nuclear waste dump: he questioned the concept that it would bring economic benefits to the community, saying that he himself had many tickets, but had never been able to find work in the mining industry.

Brachina Gorge, Flinders Ranges

On the road back we travelled to the beautiful Brachina Gorge, which offered us another glimpse of the rugged beauty of the Flinders Ranges. We then drove back through Port Augusta to Adelaide, onwards to Canberra - meeting the violence of the storm for the third time on the road: a van door slamming in the wind got the better of Alex's hand, who ended up with some broken bones in Balranald, then Hay, then Wagga-Wagga hospitals to get fixed... But that's another story. We will go back to South Australia, but after 10 interviews with some amazing people, and incredible footage of country, we feel that we have enough material to produce a film which we hope will attract some international attention onto what is happening in South Australia at the moment.

The nuclear waste dumps issue should be something that all Australians should fight, shoulder to shoulder, with Aboriginal people - for all future generations. Many thanks for following our journey.