In November 2016 I had the amazing opportunity to travel to Kolkata, India, to attend a two-week intensive course on Environmental Humanities: Ecology, Culture, Intervention, led by Professor Stephen Muecke (UNSW) and Dr. Nilanjana Deb at Jadavpur University.

Prinsep Ghat, Kolkata

Photograph by Shantam Basu

I felt that this course would help me pull together my last discussion chapter for my PhD work with Nyikina women in the Kimberley, as our collaboration for the past ten years has revolved around conflicting notions of development and the environment. And I was not disappointed! Jadavpur University’s multi-disciplinary approach on the topic of Environmental Humanities is innovative and refreshing.

This was my first visit to India and an absolutely wonderful experience on every level. Everyone in the course, staff and students, went well and truly above and beyond the call of duty to make me feel welcome there, as the only international visitor apart from Professor Muecke. Dr. Nilanjana Deb took a lot of time off her incredibly busy schedule to introduce me to her beautiful city, as did other students in the class. Scholars, many of them Indigenous, had come from all over India, to learn but also to share what was happening in their respective homelands.

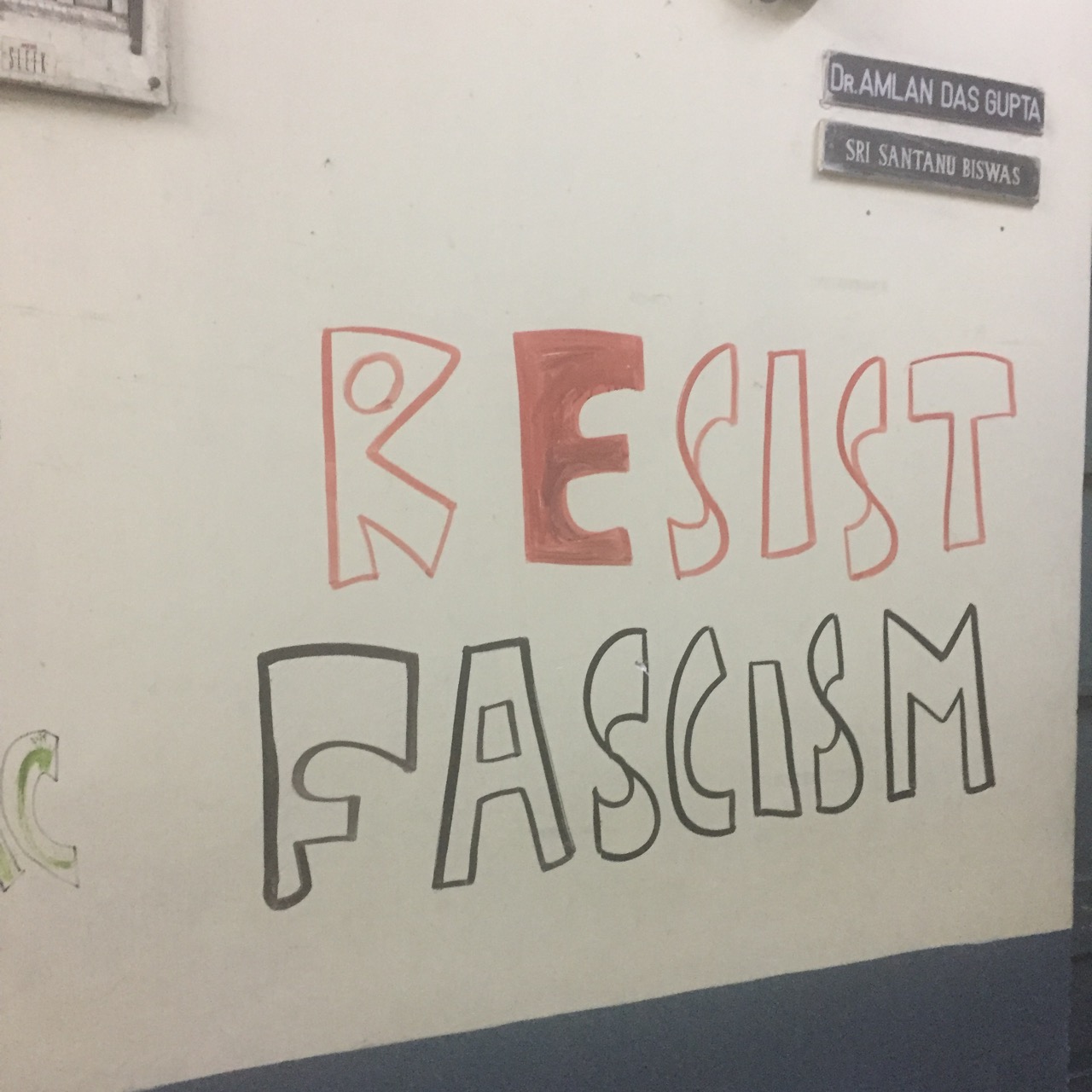

Jadavpur University is known in India to be quite an activist university, where students’ movements are very strong, as reflected in the graffiti work adorning the corridors of the English Department, where we were based.

I felt very privileged to be invited to hold an informal session with research students and staff from the Department of Comparative Literature, which houses the Centre for Canadian Studies, and to present one of the lectures for our course, based on my research work and the current situation in the Kimberley, during which I showed our film, Three Sisters, Women of High Degree. As part of the course we also undertook two field trips, one to the Kolkata ghats on the Hooghly River, a tributary of the Ganges, and to the flower markets, and another to the East Kolkata Wetlands.

Department of Comparative Literature, Centre for Canadian Studies, Jadavpur University, Kolkata

East Kolkata Wetlands

I have included below two ethnographies I wrote whilst in Kolkata, as well as the photographs that accompany them. I feel they best reflect my experience of the great City of Joy. I am truly grateful for all the amazing people I met and hope to continue working with for a long time to come. I have been invited to present at an international conference hosted by the Centre for Canadian Studies next March (via Skype), and to write an article for the Project E-QUAL Newsletter (an international collaborative project in the five key areas of Critical Thinking, Cultural Studies, Human Ecology, Natural Resource Management and Sustainable Development). And so the river stories from many peoples and countries continue to be disseminated around the world…

On an evening walk near the Hooghly River, Dr. Nilanjana Deb read us this translation of the monument beside the river:

"This monument is dedicated to the well-being of fish. It says that life, our life, is dependent on water, and to be aware of the importance of the beings that live in water. It is something that all of us should work towards, to increase awareness of our relationship with water creatures, and this is dedicated to them".

An Ethnography of a Pedestrian Crossing in Kolkata

Having been in India for all of three days, I am aware that my observations will remain somewhat superficial – I have not yet ‘learned to see, think, feel’ (Marshall, 2015), and appreciate the full reality of crossing a busy Kolkata road with the eyes, and ears, of a local. Participant observation (Malinowski, 1922) is useful, within limits – I must also acknowledge that as the ethnographer, I am very much an outsider in this space.

At first glance, there appears to be no rules. Through my Western gaze, the crossing looks like a noisy, disorganised, chaotic space. People cross whenever or wherever they have an opportunity to cross. This often involves much zigzagging between vehicles – it is never a straightforward affair. They may choose to use the crossing, but mostly, they don’t. Pedestrian red or green lights do not seem to be a factor in the slightest way. Unlike in Australia, where many cross the road while texting, or chatting on their smart phones, crossing a road in Kolkata requires utmost attention and concentration. Vehicle trajectories are unpredictable: they may change lanes at any moment. Because of this, and of their sheer number and mechanical power, one would think that vehicles are in very much in control of the situation.

Most people will wait for a temporary break in the traffic, make a dash to the middle of the road, and stop there until they can cross to the other side in a similar fashion. Others will attempt to cross, only to step back when prompted by an angry honk, and a car stopping abruptly within millimetres of their person. Some are more patient: perhaps they have more time. They wait longer, and proceed to walk to the other side, whilst talking to each other, but never taking their eyes off the road. Others bravely defy traffic and make a run for it on their own.

It seems that there is power in the masses – if a large group of people decides to move forward as one, vehicles do not have a choice but to let them cross. Care for the youngest and oldest is shown at all times: young children hold hands together or with their mothers; old people with the younger people accompanying them. A stray dog had also apparently worked out that it was indeed safer to cross the road in the company of humans than by itself. Having said that, one old man single-handedly managed to stop one bus, a car, and two auto-rickshaws by slightly raising his hand at them, walking slowly but confidently in front of the traffic with his four-leg walking stick, without even glancing at the drivers.

The chaos is only a superficial, first-hand impression. At no point did I feel unsafe crossing the road, particularly in the company of others. There is a prevailing sense of solidarity amongst pedestrians – haphazard groups form to cross the road and instantly disperse once on the other side, each person heading to their own destination. Vehicles will always honk as if in protest – but they will stop and wait.

Reciprocal recognition (Hage, 2000) occurs firstly between the pedestrians themselves: realising, perhaps unconsciously, that there is safety in numbers, if only momentarily, they support each other tacitly – ephemeral solidarity being, surely, the best strategy of survival for all on the crossing. It makes no doubt that drivers also recognise, and ultimately respect pedestrians, particularly the most vulnerable – if a frail old man can stop the traffic with a slight wave of his hand, the ethical foundations of the society I am observing cannot be questioned.

The mutual obligation between drivers and pedestrians appears to lie in the assumption that they are all trying their best to do what they are supposed to do at this particular moment in time, fulfilling the responsibilities they each have in society. Pedestrians, however haphazard their crossing of the road may appear, have an obligation to be careful, and to not push the limits of safety too far. Drivers, on the other hand, have a responsibility to not misuse the power that they have been given by having control of a motorised vehicle.

A busy pedestrian crossing in Kolkata reminds us that tacit trust is the foundation of ethical society: if each individual recognizes the others’ existence, and fulfills their own responsibilities, everyone, including humans and vehicles, can coexist peacefully, and get on safely with their day - including the stray dog.

A Photographic Essay of the Kolkata Ghats

Baghbazar Ghat, Kolkata

Baghbazar Ghat is an old ghat, as yet apparently untouched by modernisation, unlike other ghats along the Hooghly River in Kolkata. Wide steps leading down to the Hooghly are covered in slippery, thick, pungent river mud. Flowers, leaves, colourful receptacles, tree branches, water hyacinths, shreds of vivid materials, dismembered idols, plastic plates and cups, pieces of polystyrene, and plastic bags, mingle in untidy heaps, deposited there, seemingly haphazardly by people, storm water, or the river itself. Sadly, worshippers have recently taken to placing their flower offerings to the dead in plastic bags.

The Hooghly, a tributary of the Ganges, is a place to farewell, revere, and remember the dead – small, spontaneous shrines flourish in elaborate niches at the top of the ghat. Paintings and representations of Shiva adorned with flowers, necklaces, and bright fabrics, sit side by side with a statuette of his son Ganesha, the God with the elephant head, and a series of wooden, brightly painted mask figurines. Another niche below contains the statue of a cobra snake – a symbol of death and rebirth, perhaps? For at the ghat both life and death are closely enmeshed – and the Hooghly is the link between both. Nearby markets sustain the livelihoods of the people who survive, from death itself – from selling balls of river mud for ceremonial practices, or the plastic containers that will allow worshippers to take some of the holy river water back home, through to the idol figurines, necklaces, jewellery, flowers, and clothing the people will need to perform those death rituals.

At the Nimtala Cremation Ground a cremation ceremony is about to start. People are waiting inside, while the wood is being carried in. Here the cremation still occurs traditionally, although many crematoriums around Kolkata have now opted for electricity. The ground itself is wide open, looking out onto the river, and houses the Tagore’s Samadhi Memorial – a sense of peace and quiet prevails. People say that when the smoke comes out of the chimney, the soul of the dead person has been released. Unlike in Western countries, where death is mostly hidden and feared, death here is everywhere: the hearses transporting the dead have glass panels, and the person awaiting cremation lays covered only by a thin, colourful cloth, and flowers – this visibility perhaps a better way of accepting death as part of the journey of human life. On the day of our visit, the relative quietness and peace of the cremation ground is interrupted by a string of announcements and speeches blaring out of a loudspeaker just outside. A celebration is underway, officials at the ready in their bright white uniforms, a small crowd gathering: they are marking the anniversary of the first air-conditioned hearse – even the dead can travel in comfort now, whilst producing their own greenhouse emissions…

The Nimtala Cremation Ground, a place of death, spawns life. Ghettos of metal and timber huts sprawl near abandoned warehouses, temporary lodgings only: many traders have a house in a village somewhere, and have come here to earn a living. Like at Bahgbazar Ghat, people have set up shops to cater for the dead – and the living. The usual trades have sprung up: idols, jewellery, flowers, clothing, food and drink stalls. Reflecting changing times, some have also been quite imaginative – a photographer has set up shop, taking photographs of the dead and their family just before cremation. He is said to be doing very well.

The Art of Making Masala Tea

At a small hut near the Nimtala Cremation ground a crowd has gathered. People take their seats on wooden benches expectantly. An old man is sitting in a small, dark recess, in the midst of old pots and bottles. A painting of Shiva, the all-powerful god, at the back of the hut, appears to watch over the proceedings. A boiling pot sits on a bed of hot coals. A small electric fan on the ground, controlled by a switch at the back of the man, controls the temperature of the coals, for it must be just right. A mixture of milk, water, and masala are boiling in the pot. The old man is stirring it quickly. When it comes to a boil, he takes it off for a few seconds – then puts it back on, bringing it to the boil slowly again. The old man adds holy basil to the mix. Flick of the switch, quick stirring, lifting – and again, several times: it is all in the wrist action. The pot is stirred again, cardamom pods added, then rose water. The sequence of events is a wonderful, rhythmic choreography, of gestures timed, rehearsed and performed hundreds, perhaps thousands of times. Nothing is left to chance. In a swift, final move, the pot is taken off the coals, another pot held in the other hand, and the mixture poured from one into the other, from high up in the air, into the pot below – to cool it down. The tea is served in a terracotta cup. Everyone sits and savours it for a few seconds, before going back to their respective occupations. An ephemeral, peaceful, quiet moment shared by friends or strangers, away from the chaos of the street.

Across the street, a man is sitting in the sun, on a rug on the ground. He is reading his newspaper. At first glance a newcomer like myself may not realise what his trade is. On closer inspection, homemade cards lie, in a line, face down beside him. Almost unnoticeable at first glance, a small cage sits in a corner of the rug. In it, a lively parrot. It has been trained, perhaps through gentle persistence, and food rewards, to pick six cards for the odd tourist, or passer-by. The man is a fortune-teller, and his companion the parrot, the source of his livelihood. Unlike the masala tea maker, the outcome of this activity is much less certain. In spite of the offerings of seeds, the parrot is not always willing to work – sometimes it decides that now is not the time, and the fortune will go untold, leaving the traveller, myself in this instance, somewhat disappointed, and the fortune-teller to go back to his newspaper, hoping for a perhaps more successful outcome - next time. For there is a lot of waiting at the markets – chaos suspended, for some, in the midst of the overall noisy traffic rush: sellers wait in their stalls for prospective customers; ageing, wrinkled, wiry hand-rickshaw drivers bide their time in the sun until their next ride; beggars, infirm, blind, old, or ill, stand, hopeful, with outstretched hands, on the side of the road, hoping for a couple of rupees; stray dogs and goats roam, waiting for sustenance that may never come.

Further on, and the intensity of the flower market assails the newcomer’s senses: the smell of tube roses attracting hundreds of bees, the vivid colours of the large flower heaps, the throngs of bodies in narrow spaces, the din of people calling out to each other amidst the hubbub of negotiations, the impatience of porters running up and down the alleyways, carrying their colourful loads on their heads… Wherever I go, I seem to be in the way. A man sits down, carefully threading vivid orchids onto a fine metal thread. Again, the gestures are precise, the hands self assured, the eyes never averting from the task at hand, in spite of the business of the surroundings. In the midst of animated bargaining between wholesalers and retailers, weighing, ordering porters, counting money, appraising merchandise, and more bargaining – there are hundreds like him. In this well-ordained chaos, everyone, human and non-human, has a role to perform. Bael leaves, blue flowers, and wild plants are sold for the worship of Shiva, and red hibiscus for the Goddess Kali; white lotuses, the symbol of enlightenment, will be offered to the Goddess of Knowledge, Saraswati, or to teachers and mentors, as a gift of appreciation; mango leaves are strung for home decorations; loose flowers are neatly wrapped in wet leaves to take home; tiaras and garlands await the prospective brides and grooms, while baby coconuts will be sold to hang above entrance doors, welcoming people into the home. New additions have recently come to the market: orchids, carnations, in ready-made bouquets, even artificial flowers, are now being flown in from Bangalore and other areas. This is a fluid, ever-changing space: a market stall during the day turns into a shelter at night – for many traders, this is the only place they call home. Against the original supporting structures, the colonial iron pillars, they have built brick walls and timber frames, to make the shacks more comfortable. Just outside, at the Mallick Ghat, they go about their daily ablutions, unperturbed by the traffic on one of the main Kolkata bridges, right above their heads.

Flower Market and Mallick Ghat

Sunset on the Hooghly River

At the Kolkata ghats, these livelihoods are more than survival mechanisms, perhaps also more than crafts. They are, in a sense, art forms, or ‘poiesis’ in action (Heidegger, 1977), at times relying on precise gestures, crafted and re-crafted, time after time, or at other times, simply imaginative, poetic ways of re-affirming life, or creating solace – from death. At the Hooghly River ghats, the Nimtala Cremation Ground, and the flower market, both life and death are closely enmeshed and the river provides the link between them, and people. These networked local ecologies, economies, and histories are ecosystems in their own right: they are all inter-dependent, deeply relational, and collectively produced (Haraway, 2016, p. 49). Every component needs the other – flowers, tea, humans, parrots, river, stray dogs, all need each other to function. They are sympoetic – they evolve and change with events, seasons, ceremonies, people’s imaginings – they are a tacit understanding that the river, humans, and non-humans all need each other to transcend the boundaries of life and death.

East Kolkata Wetlands